A memoir of revolution by Adam Sterns, translated and edited by Ian & Austra Hart

This remarkable document is a first-hand description of the chaos that engulfed the city of St Petersberg in February-March 1917. It began with local rioting over food rationing and culminated eight days later in the abdication of the Russian Czar. In October of that year, the Bolshevik Revolution changed the course of world history.

In February 1917, Adams Sterns was a 22 year old Latvian junior officer in the Russian Imperial Army. In his memoir he records the first stirrings of discontent among the troops, whose resentment against the officer class progresses rapidly from indiscipline to insubordination to murder. Sent into the city to restore order, his Company is ambushed multiple times by royalist police and gendarmes. His platoon of soldiers is progressively depleted by desertion and by deadly Maxim machine gun fire, until he finds himself alone, forced to conceal his rank while fellow officers are hunted down and murdered in the streets. Yet in the midst of this mayhem and horror, Sterns finds moments of tranquillity and even humour. His memoir covers just eight days in the year that changed the world, but it also contains insights into what Canetti described as the dynamics of crowds, some astute observations of the Russian character, as well as a graphic account of one man’s resilience in the face of a total breakdown of order and civil life.

Adams Sterns wrote his memoir in 1974 for the Latvian war veterans magazine1. His poetic title was The song of the Maxim Guns in Petrograd (“Maksimu” dziesmas Petrogradā). It is not an academic historical document — it is a personal account of a descent into hell, written from memory (presumably with the aid of his officer’s notebook) 60 years after the event. Consequently there are inconsistencies in chronology and geography as well as numerous subjective reflections on the horrific incidents he witnessed. Sterns translated his magazine article into German for his sons, who did not speak Latvian. He titled this version EYEWITNESS AND CAMPAIGNER IN THE STREETS OF PETERSBURG, DURING THE FEBRUARY REVOLUTION of 1917.

In our English translation we have slightly rearranged the narrative of Adam Sterns’ typescript to fit the chronology, and have organised it under section headings. We have also added pertinent explanations as well as some footnotes to provide context for the reader.

CONTENTS LIST

- THE SONG OF THE MAXIM GUNS

- SOLDIERS & OFFICERS the breakdown of army disciplinei

- SAILORS The sailors from Kronstadt Naval Base are the first to join t

- THE ROAD TO PETROGRAD: Sterns leads his company to the city to help restore order and meet the first resistance from Maxim-armed gendarmes

- ISMAILOVSKY PROSPEKT An procession of students is attaked by the gendames and Sterns’ soldiers (now reduced to a platoon) take out several machine gun nests in the church

- THE OFFICERS CLUB: A surreal scene with senior officers and their families feasting and dancing while murder erupts in the streets.

- LOOTERS: Sterns leaves the officers club and follows a gang of soldiers and civilians looting houses and shops

- COSSACKS: A band of drunken Cossacks arrests Czarist officers and hacks them to death in the street.

- DELICATESSEN: Sterns joins a crowd breaking into a delicatessen and only escapes being crushed by deception

- OBVODNIY CANAL: A horrific scene in whih senior officers and class traitors are beaten and drowned under the ice.

- HOTEL: An attempt at organising food and shelter descends into chaos.

- HE’S A PHAROH!: Middle- and Upper-class people are denounced and killed. Tanks are deployed against the last gendarmes

- THE TOURIST: Sterns take the opportunity to Visit the Hermitage and the Zoo.

- UNEASY PEACE: Surviving troops have reassembled at Army Headquarters. One of Sterns’ old enemies is punished. Sterns is offered command, but declines it and decides to return to Latvia.

- POSTSCRIPT. The mass burial in The Field of Mars.

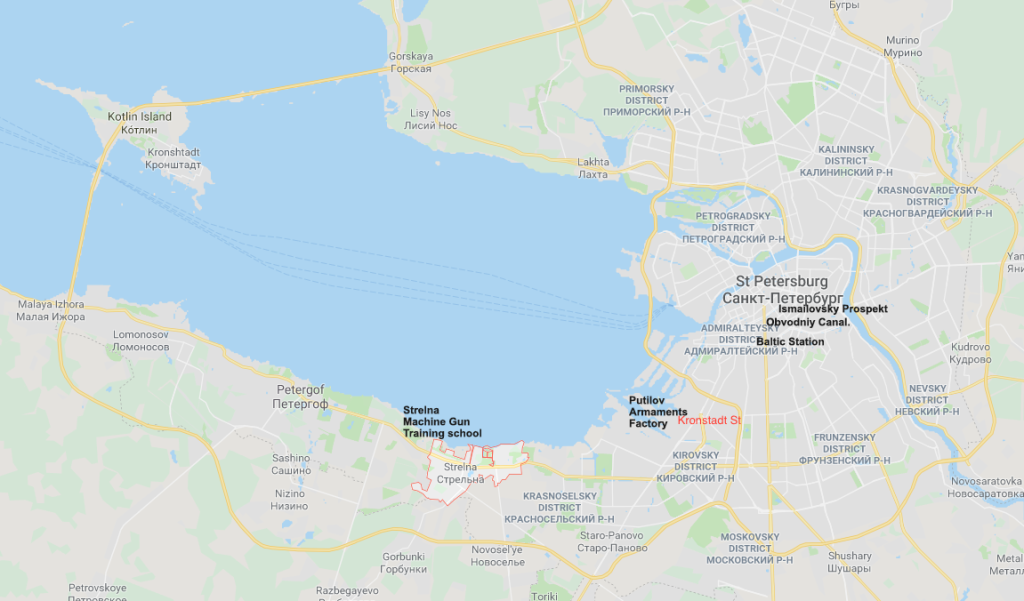

- MAP OF ST PETERSBURG AND GULF OF FINLAND

- CHRONOLOGY OF THE FEBRUARY REVOLUTION

THE SONG OF THE MAXIM GUNS IN PETROGRAD

My name is Adams Sterns. I was born in the Latvian province of Russia. At the start of the Revolution of 1917 I was a Lieutenant (Porutschik) in the army of Czar Nicholas II. This document is my eye-witness account of what took place in Petrograd in the month of February 1917.

SOLDIERS & OFFICERS

Russia entered the war severely under-prepared and poorly led by its senior officers. By 1916 there was a noticeable deterioration in military discipline. Soldiers were often insubordinate towards their officers, sometimes with murderous consequences. I witnessed a tragic incident when I was serving in the 2nd Infantry Battalion near the village of Lebedyan (south of Moscow) where we were training the soldiers to handle bayonets. Straw bags representing enemy soldiers hung in wooden frames and, at an order from the instructor, each soldier would run in and stab the sacks with his bayonet while screaming loud obscenities. One particularly officious instructor was dissatisfied with a soldier’s mild oaths and lack of aggression. He ordered the trainee to repeat the exercise again and again, The soldier became so infuriated, he stabbed the officer in the chest with his bayonet, killing him instantly.

A few weeks later, I witnessed another fatal incident: an officer arrived at the barracks gate unexpectedly and ordered the guard to admit him at once. The guard replied “What’s the hurry, mate?” “Address me properly!” shouted the officer and slapped the guard across the face. The guard turned his bayonet on the officer and fatally wounded him. The sergeant in the guardhouse emerged waving his sword, but the guard stabbed him as well.

Two weeks after that incident I was transferred to the 2nd Machine Gun Training School in Petrograd. Our headquarters was on Kronstadt Street, but our school was located in the village of Strelna3, 21 km from the city on the Bay of Finland. The commander of the training school was Lieutenant Rakey, an arrogant, conceited and cold-blooded Polish officer, who habitually sported a riding crop under his arm. In those days soldiers were required to address lieutenants as “Your Grace”4 (Ваше Благородие), but Rakey demanded that he should be addressed as “Your Lordship” (Ваше Высокоблагородие), an honorific reserved for aristocrats and officers of higher rank (who were often aristocrats).

When Rakey was supervising exercises and overseeing the training, he would punish any soldier he noticed doing even the slightest thing wrong. If the soldier showed Rakey fawning respect, he would get off with a tongue-lashing, but if the soldier had the insolence to address the Pole as “Your Grace” he would receive a cut across the face with the ever-present riding crop.

A bitter argument about Rakey’s affectations blew up between a lower-ranked lieutenant and the Polish commanding officer. The young officer was very correct, decent and respected by his peers, but after unrelenting persecution by the malicious Rakey he committed suicide. He left a note complaining about the impossible situation that Rakey had put him in.

SAILORS

A confidential memo was circulated among the officers that revolutionaries were planning an armed insurrection in Petrograd in the near future. In February, a workers’ uprising against the Czar erupted at the Putilov Iron Works in Petrograd. We heard rumours that several army and navy divisions had sided with the workers so, as a precaution, all leave was cancelled. The soldiers on guard were replaced with officers, all weapons were locked in the armoury, and the men were confined to barracks with officers guarding the doors and windows. At meal times the soldiers were marched to the mess in small groups.

On the morning of 28 February5 it was snowing and very cold, and unusually quiet. All traffic seemed to have stopped and we feared the worst. At 8:30am three military trucks containing sailors from the Kronstadt Naval Base6 pulled up outside the gates of the camp. Maxim machine guns mounted on the trucks were trained on the guard house. A voice shouted through a megaphone: “Friends, join us!” and a burst of machine gun fire erupted over our heads. We officers were in an impossible situation: our machine guns were locked away and it was obvious that resisting the soldiers with rifles and bayonets would be suicidal. What’s more, our commanding officer, Lieutenant Rakey, was nowhere to be seen.

The megaphone barked again: “Officers, release the soldiers and march with us to Petrograd!” We had no choice: we grounded our rifles while the soldiers behind us smashed windows and door frames to escape from the barracks. They broke open the armoury and took whatever weapons they could carry. It was chaos.

Eventually the sailors fired another machine gun salvo to restore discipline. They ordered us to form up on the parade ground, with the officers in front. The sailor with the megaphone gave another order: “Officers! Whoever is with us, step forward!” Lieutenant Knass, who was known to be related to Czar Nicholas, was the first to step forward and we all followed. The sailors then invited the soldiers to separate the good officers from the evil ones. Any officer denounced by a soldier was surrounded, roundly cursed and in some cases struck with rifle butts. The scene became rowdy and some soldiers begin firing shots into the air. Had Rakey been present, I doubt he would have survived the soldiers’ revenge.

The sailors let our soldiers have their heads for the next hour, until no officer felt confident that he would survive. But finally the sailors restored order again and invited the soldiers to pick out the “good” officers they would be happy to serve under. The soldiers passed through the line of officers again, this time asking each of us his name and writing it down, then they went into a huddle to consider. They argued loudly, but eventually chose the acceptable officers. The sailors gave the command “At ease!” and solemnly told the soldiers that they were now under our command and should follow our orders.

The sailors ordered our company to proceed to Petrograd where fighting had broken out, and help keep order. We issued the men with rifles and bayonets and formed them into a column on the road. The officers mounted on horseback led each platoon, and we set out for the city. Some of the sailors marched with us for a while, but soon they became impatient, re-mounted their trucks and overtook our column. We were soon alone, marching into who knew what situation?

THE ROAD TO PETROGRAD

The day turned out fine and sunny and the men began singing as we progressed along the empty road. At the outskirts of the city we were greeted by a crowd of joyful citizens waving banners and shouting “Long live the revolution!”. They fell in beside the column as we swung into Prospekt Stachek and our voices echoed off the walls of the Putilov Iron Works7.

The atmosphere of celebration and the display of military discipline anruptly came to an end when machine gun fire burst from the factory windows. Our soldiers had been taught the drill when under machine gun fire—hit the ground and lie as flat as possible—but the civilians marching with us reacted instinctively and made panic-stricken attempts to escape along the street. They were mown down mercilessly by the raking fusillade of bullets. My horse was hit—it reared up and threw me to the ground, where I lay uninjured as the other horses and fleeing crowds jumped over me. Our soldiers fired at the factory windows as they crawled on their stomachs to take shelter along the side of the building, but anyone standing or running was a target. Using my whistle and hand signals, I led the soldiers along the wall to the corner and we made our way around to the unguarded rear doors of the factory and smashed our way in.

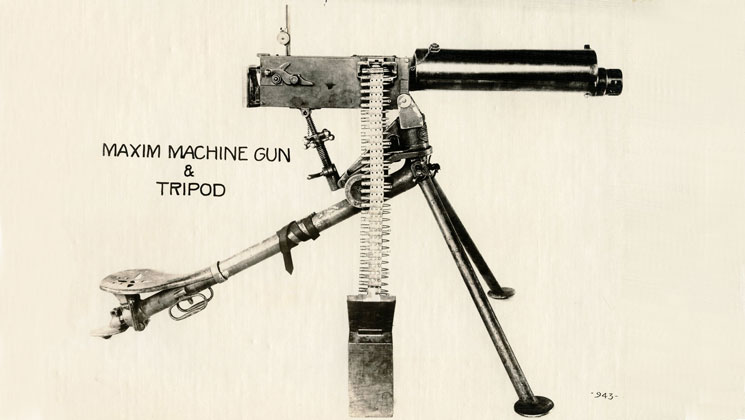

A Maxim gun is a deadly weapon—it can fire up to 600 rounds per minute, but it is heavy and hot and needs to be mounted on a tripod. It requires a crew of at least three to set it up and operate it efficiently: one to aim and fire, one to feed the ammunition belt, and one to maintain the water cooling system. Our men were trained machine gunners and knew that once a Maxim has been set up it takes time to change the firing direction. Consequently, we had little difficulty outflanking the machine gun crews stationed at the windows overlooking the street.

We captured eight machine guns and shot the Czarist gendarmes who were manning them. Stachek Street was littered with dead and wounded civilians as well as many of our men who had fallen or were wounded. When we reassembled, we realised that the Russian officers had disappeared and I was in command of what remained of our company. None of us was familiar with the streets of Petrograd, but I had a street map in my kit and I ordered the column to head for our company headquarters in Kronstadt Street. When we passed the Baltic Railway Station, the thought crossed my mind that a wiser course might be to follow my Russian colleagues’ example: abandon this march to nowhere and catch a train home to Latvia, but I rallied the men and we continued our progress across the Obvodniy Canal bridge and into the wide, impressive, but eerily empty Ismailovsky Street

ISMAILOVSKY PROSPEKT

About a mile along the boulevard, we halted to inspect an impressive military monument, the height of a five-storey building, constructed from tier upon tier of cannons and topped by a bronze angel holding a wreath8.

We broke out the last of our rations and were passing them around when we saw a large crowd of civilians approaching along the boulevard. The parade was led by students carrying revolutionary banners and waving red flags. Some of the marchers were also waving hunting rifles and pistols, and I was concerned they might regard us as hostile, so I commanded my men to move to the pavement and shoulder arms. The students cheered and shouted to us to join them, but when they were about 30 metres away, machine gun fire opened up from the buildings on both sides of the road. I shouted “Maxim guns!” and my soldiers immediately threw themselves down in the snow and ice.

The demonstrators ran in all directions. Some of them stopped and fired their weapons at the windows, but they stood no chance against the machine gun fusillade. I ordered my men to pull back to the shelter of a wall alongside a corner house, which seemed to be out of the firing line. I realised we would have to fight our way out of this and I ordered the men to load their rifles and attach bayonets. I had a rifle with a bayonet in my hands, and a machine gun slung over my shoulder with 250 rounds.

The house opposite had a kiosk attached, with icons displayed on top, surrounded by coils of barbed wire. I crawled up to the wire to try and locate where the shooting was coming from and spotted a machine gun emplacement in a third-floor window about 120 metres away. I pushed my rifle through the wire, took aim at the window and fired. The machine gun stopped shooting, which possibly meant I had hit the gunner. I was wearing a Russian papacha (high fur cap) and I carefully raised my head above the wire to check, but the firing recommenced and a bullet knocked the cap off my head. When the shooting stopped again, I snatched up my cap and ran back behind the house just as another machine gun started up behind me. We crouched behind the wall as bullets whistled just 25-30 cm over our heads. They shredded the plaster and we were showered with cement and splinters of brick. Once again we were forced to lay flat on the ground. After ten minutes or so, the Maxim fell silent, probably because the gunners assumed we were all dead.

I was soaking wet and covered in sweat from the excitement as I looked back over the street. Several hundred demonstrators lay dead in the road, and the snow was red with blood. There was a battle going on all around us—we could hear the ‘crump’ of light artillery and the explosions of hand grenades coming from the neighbouring streets. The Czarist gendarmes were concealed in churches, basements, behind the windows of houses and even on rooftops, from which they picked off anyone who moved in the streets.

The Maxim gun opened up again intermittently, even though there seemed to be no targets left alive. Perhaps they just wanted to hear the sound of their gun firing. My last NCO, Corporal Kovy got to his feet beside me and immediately collapsed, hit by a hail of bullets. I saw that the shots were coming from a Maxim gun at one of the church windows across the street. I put my rifle to my shoulder and fired at the gunner – his head disappeared and the gun fell silent. Full of anger, I shouted to my soldiers to follow me, jumped up and ran towards the church9. To tell the truth, I was not sure my soldiers would obey, but I looked back to see they were hot on my heels. We were just metres short of the church when the Maxim started up again. We threw ourselves onto the snow and lay flat, inching our way forward every time the shooting paused. The gendarmes must have guessed that we planned to circle to the back of the church, so they began raking the street with bullets, and we lay prostrate, imagining ourselves nailed to the road.

I knew that it took an experienced gun crew 45 seconds to change the magazine on a Maxim, so we stayed immobile until the gunner had emptied the ammunition belt. Our lives depended on the timing, so we jumped up and ran like the wind to the church wall. Fortunately, my calculation was accurate and we made it before the Maxim began firing again. The windows were around 3 metres from the ground, which meant that, crouched against the wall, we were out of their firing line. I asked my soldiers whether any of them still had a hand grenade. Fortunately they had several and I took three (to this day, I still wonder why the soldiers entrusted me with them). To reach the window we would have to form a human pyramid: two soldiers stood side-by-side and I ordered a third soldier onto their shoulders. He did it without a second thought, shoved the grenade through the smashed window and jumped back down quickly. After a few anxious seconds, the grenade exploded and the gun fell silent.

We approached the front door of the church, but it was locked. We heard shots from the windows in the side streets, and nearby another Maxim gun barked, which meant there were more armed gendarmes inside. I left two soldiers at the front and went around to the small back door, which was also locked. It was not as strong as the front and we managed to bash it open with our rifle butts. I told the soldiers to lie on the ground and cover the doorway, then I went back to the front door and ordered the soldiers there to strike the heavy door with their rifle butts as though trying to bash it open. My plan was to divert the attention of the gendarmes inside from the back door. The plan worked: a Maxim barked from inside the church and its bullets pierced the door, but we had already jumped back against the wall to one side, and the bullets missed us. I told my men to start shooting at the door to keep the gunners engaged, then I ran back to the rear door and we sneaked into the church. We found the Maxim gun manned by four Czarist gendarmes with their backs to us, still firing at the front door. We took them by surprise and that was the end of the fight. We found four more dead gendarmes beside the first Maxim gun, killed by our hand grenade. We destroyed the two machine guns so that no one else could use them and we searched the whole church, but there were no more enemies inside. We collected up the remaining ammunition and left the blood-spattered walls of church behind us.

THE OFFICERS CLUB

As we looked out into Ismailovsky Street, I estimated about 300 bodies lay in the blood-drenched snow, most of whom were civilians, but I saw that many of my soldiers lay amongst them. I was worried we may become trapped in the church and scanned the streets around us for an escape route. Not far away was a solid, four-storey building with intact windows, which indicated that there were probably no machine gun posts inside.

We set out to cross the wide boulevard, but before we reached the middle, the firing started up again—this time from our right, and we came off the worse for it. Before we could hit the ground, more of my soldiers lay dead or wounded. I signalled to the men to crawl on their bellies towards the front steps of the building. Our painful progress was accompanied by the sounds of artillery and heavy fighting in the nearby streets. When we reached the opposite side of the road, the Maxim on our right opened up again. I lay in the snow and observed the front door to the building: it looked more decorative than secure, with glass panes set into the wood. I waited until the machine gun fell silent again, indicating a 45 second re-load, and I shouted to the men to follow me and we ran for our lives towards the door. It was locked. I smashed the flimsy door handle with my rifle butt, the door flew open and we tumbled inside. We found ourselves in a marble corridor, safe from the guns for the moment, but I saw that only half a dozen solders had managed to follow me10.

We were in a corridor which ended in a marble staircase carpeted in a dark brown, expensive material. I unholstered my service pistol and ordered my few remaining soldiers to attach their bayonets and follow me. We moved slowly and carefully up the steps to the second floor, where we found ourselves in another wide corridor—brightly painted and also richly carpeted—which led to a double door with brass fittings. I ordered the soldiers into formation, but before we could approach the door, it was opened from inside by a very surprised soldier. I asked him who was in the building and he stammered out that this was an officers’ club and the room behind him was full of officers. I told him to go back inside and announce me.

The soldier went away for a few minutes and when he reappeared he gestured us to follow him. He pushed open a second door and I entered the room accompanied by my small, but armed and alert, troop of soldiers.

After the mayhem in the streets, we felt as though we had stepped through a portal into another world. The ballroom was lavishly furnished, with Persian rugs on the floor and paintings of aristocrats and officers on the walls. The black drapes curtained the tall windows, and sparkling chandeliers lit the room. We stared in astonishment at the long table in the middle of the room where a cornucopia of exquisite delicacies was laid out along with bottles of liqueurs, choice wines, flavoured vodkas and champagne in ice buckets. The room was crowded with officers of all ranks, from Lieutenants to Generals, as well as a number of elegantly-dressed ladies. In the corner, a balalaika and accordion ensemble was playing a popular folk tune.

A hushed silence fell as we stepped into the room and everyone turned to face us in expectation and fear. I was polite and apologised for the disturbance, but inwardly I was revolted at the decadence of the scene: while thousands were dying in the street, these officers were holding a party! My face must have betrayed my anger.

A captain stepped forward, clicked his heels and demanded to know what my business was: “Are you on the side of the Czar or the revolution?” he demanded.

I replied with my own question: “Captain, was it you who ordered hoodlums to desecrate the churches and slaughter innocent people in the streets?”

The captain sat down abruptly and it appeared that no-one else had any further questions. I announced that I was not a revolutionary—my men had marched to Petrograd to help keep order in the streets, but we had been shot at and forced to defend ourselves, and many under my command had been killed or wounded. I asked the captain what he would have done in my place and whether he had personally taken any action to deal with the situation outside.

The captain became conciliatory and said, “Please Mr Porutschik, sit and eat and ask your men to join you at the table.” I was surprised that my soldiers were being invited to eat at the same table as an officer—something that had been strictly forbidden in the past. We were all famished and tired, but for safety, and to maintain decorum, I posted a soldier (with a plate of food) to guard the door.

We helped ourselves to pelmeni and ikra, pickled herring and French pastries, jellied khodolets and crystallised fruits; we were offered brandy and liqueurs, but I told my soldiers to confine themselves to kvass as they may need their wits about them later. (But I must admit I could not resist a small glass of Riga Balsams—Latvia’s national liqueur.) The officers crowded around us, anxious to discuss what was happening. Some took the position that the troops in the street should demand the government immediately make peace with Germany. Others argued that the Latvian battalions on the Riga front should initiate a peace treaty.

“Why is it up to the Latvians?” I asked, “Surely they are part of the Russian 12th army?”

They answered that the Latvians are renowned for their bravery, and their combat skills are respected throughout the Russian army. I was surprised to hear Russian officers praising the Latvian divisions so highly. My Russian was fluent, without regional accent, so I did not think they suspected I was Latvian—but perhaps my fondness for Balsams had given me away! I replied that in my opinion the Latvian army did not care one way or the other who signed the treaty.

They speculated on what the revolutionaries wanted—was it simply peasant discontentment, which might be put down with a food distribution or money; or was the uprising orchestrated by outside forces? If soldiers were mutinying against their officers, might the Czar be under threat, or even forced to abdicate?

I answered: “All the signs outside on the street suggest the resentment against authority runs very deep. I would not be surprised if it comes to the Czar being deposed.”

The questions and arguments grew heated, but my men and I were exhausted, and eventually I asked, “Gentlemen, is there somewhere we can lie down and catch some sleep?” The officers showed us to an adjoining room with a divan. I ordered four soldiers to guard the door in two hour shifts and I lay down with my uniform on, but I took the precaution of removing the bolt from my rifle and concealed it under my pillow, together with my pistol. It was still daylight outside, but our first day of the Revolution was almost over.

When I woke it was dark, but the party was still in progress in the adjoining room. I felt very uneasy and I worried that accepting the hospitality of the officers might be more dangerous than going back onto the streets; a feeling reinforced when I discovered that only one of my soldiers was on guard—the others had deserted. In the previous day’s skirmishes the Russian officers had been the first to disappear, and I decided that I needed to disappear as well. I confided my fears to my last loyal soldier and he advised me to change out of my officer’s uniform and dress like an ordinary infantryman. The roistering officers in the ballroom were of the opinion that if I gave up my uniform I would lose all respect. Some of their soldiers remained and one was willing to sell me his greatcoat, another sold me his hose and another his hat. I pushed my lieutenant’s epaulets deep into my trouser pocket, concealed my pistol beneath my coat, and hung a rifle and ammunition from my shoulder. When I thanked the officers for their hospitality they laughed, and when I saw myself in a mirror I joined the laughter, but at least my bedraggled appearance was unlikely to arouse suspicion outside.

Maxim guns were still barking in the distance when my last soldier and I set forth into the street in the dark night. We kept close to the walls, not sure where we were heading.

LOOTERS

Trains were intermittent, but before the revolution broke out large numbers of armed troops had arrived in Petrograd and these soldiers, like us, were unfamiliar with the city. They had been met with machine gun fire and were now leaderless because their officers had deserted or been shot. The trams weren’t running, and everyone was on foot.

We had walked just a few hundred metres when we came upon a group of soldiers and civilians whispering amongst themselves, then they set off along the street and turned at the intersection. We followed them, curious to see what was going on. The soldiers broke up into groups of three, accompanied by several civilians, and they began breaking into the houses along the street. It seemed we had joined up with a band of looters. Without warning, a Maxim began barking again and the group we were following found themselves under fire. In the darkness of the night I could make out muzzle flames in the basement window of a house. My soldier still had two hand grenades, so I advised the group to throw themselves on the ground and my soldier and I ran forward and flattened ourselves against the wall. We waited for the Maxim to fire again so we could locate its exact position, but it remained silent, probably waiting for us to give away our position. I fired a shot into the air and the Maxim started up again. We crept along the wall to where we estimated the gun to be and I pushed the hand grenade through the window. After a few seconds we heard the explosion and the gun fell silent.

We came to a large set of entrance gates with a sign indicating it was a bakery11. The gates were locked, so we boosted one-another over the wall into the yard. We quickly cased out the rear of the building and found an unlocked door. We entered slowly and carefully, but all the rooms we inspected were empty. It was dark inside and I had lost touch with my soldier. I called his name, but there was no answer so I went back out into the yard to look for him. It was ominously quiet and I had a sense that there was something wrong. Suddenly, shooting started up inside and the soldiers and civilians ran back out. I shouted, “Come on! Head for the bakery!” We all ran to the main entrance on the other side of the yard. The first room we came to was an office, where files and other papers were scattered across the floor. In the largest room we found a row of industrial electric bread mixers—some of them still contained lumps of sourdough as hard as stones. We searched the whole factory, but there was nothing to eat, or worth stealing. The soldiers and the civilians with weapons began shooting in the air out of frustration. I didn’t dare try to establish order because it would have given me away as an officer.

It was very cold, and I still hadn’t found my soldier. A few of us returned to the office where we had seen an old-fashioned cast-iron stove. There was no wood, so we burned documents and books to keep warm. I spread out some office paper on the floor to make a bed and lay down and was asleep in minutes.

When I woke, it was daylight and most of the others were laid out and snoring around the cold stove. I was hungry, so I went back into the bakery one more time to look around in the daylight. It had obviously been cleared out days earlier and there was nothing to eat, so I decided to return to the Officers’ Club.

Most of the bodies in the street outside the building had either been cleared away or were covered by a fresh layer of snow. I entered the front door unchallenged and mounted the stairs, but when I opened the doors to the ballroom the sight that greeted me was terrible: the windows, the piano, the chandeliers, the portraits, the furniture—everything had been totally smashed. Broken glass and crockery littered the floor and there were bloodstains on the walls.

I counted myself lucky that I had abandoned the officers club when I did, even if I’d had to spend the night with a gang of looters.

COSSACKS

I was alone now, and like many others I started wandering aimlessly through the streets of Petrograd trying to keep warm and away from trouble and constantly on the lookout for something to eat. I crossed many streets, using my map to orient myself whenever I came upon a memorial or famous building. I found myself in the midst of a crowd of soldiers and civilians pointing and laughing at some kind of street performance. About 20 drunken Cossacks12 were gathered in the roadway, some were singing, some were attempting to perform their famous Hopak dance, others were waving their sabres in the air. My instinct told me to avoid them, but as I turned to leave, two armed soldiers appeared leading a man wearing a plain fur coat and hat. When they brought him to a halt before the Cossacks, the laughing and dancing stopped and there was a terrible silence. The Cossacks dismissed the two guards, then they ripped the coat and hat off the prisoner, revealing a police uniform underneath.

I could not believe what happened next.

The Cossacks drew their sabres and cut the prisoner into a hundred pieces while they swore terrible oaths in Russian and Ukrainian (which I would not like to record here). They then drew their pistols and riddled the corpse with bullets. When the chambers were empty, they began hacking again with their sabres until the unfortunate policeman—admittedly he was a foe, but a human none the less—had been reduced to a mound of red meat on the pavement.

Before this first massacre was completed, some more soldiers appeared leading another prisoner. The drunken Cossacks pushed the guards aside and ripped open the prisoner’s coat to reveal he was also wearing a police uniform underneath. One of the Cossacks slammed his rifle butt into the man’s skull and split it in two and once again they began to hack the body into a bloody mess.

Watching this horrific scene impotently and in silence almost sent me mad. Instinctively, I opened my coat and reached for my revolver, but luckily I resisted the impulse to interfere. It would have been suicide, because under my soldier’s coat I was still wearing an officer’s blouse, jodhpurs and boots and carried an officer’s service pistol. I was happy to take the opportunity to vanish from this unholy scene.

The date was 29 February, 1917. It has now been 58 years, but I still have nightmares about the barbarity of the Cossacks.

DELICATESSEN

I was seriously in fear for my life and I forgot all about hunger in my eagerness to leave the bloody scene. I wandered aimlessly through the city, keeping close to the walls and scanning the windows, because at any moment I anticipated the barking of Maxim guns. While passing along a narrow street of locked shops, I came upon a crowd of soldiers who were shouting loudly and beating on a door with their fists. One or two were waving and firing off their weapons. After my previous experiences with crowds, I approached the mob slowly and cautiously until I could make out the object of their attention: they were attempting to break into a delicatessen but the windows and door of the shop had been boarded up. The soldiers were pushing and shoving and those at the front were smashing at the hoardings and door frames with cobblestones and rifle butts, Eventually the wood gave way and the whole unrestrained mob collapsed inside the shop, screaming, ranting and wrestling. Everyone was hungry and determined to grab something for himself, but the brawling was so frantic that anyone who slipped to the ground was trampled underfoot.

I was caught up in the mob and struggled to break away, but it was too late: I was pushed forward through the door. Luckily there was a very large soldier beside me, who fought like a lion, striking out in all directions with his rifle—anyone in his way was walloped. I stuck close behind him, with the consequence that I involuntarily reached the shop counter first and was squashed up against it. The shelves behind the counter were overflowing with sausages, smoked hams, cheeses, breads, dried fish and various canned goods, but there was so much pressure from behind that I was in danger of being crushed flat. I tried to shout out to those behind me to stop pushing, but it was impossible to make oneself heard. All I could do was climb up the shelves and, hanging on with one hand, I began to throw the best goods over the heads of the crazy mob and out the front door, until the shelves were empty. Now all hell was breaking loose in the alley outside the shop but, having stuffed my pockets with food, I was now able to jump off the shelves, and make my escape. I was thankful to be alive and uninjured, but even better, I had something to eat. Which meant a lot at that moment!

OBVODNIY CANAL

Over the following days, the fear of machine gun nests hidden behind windows and in cellars was replaced by the danger of gangs of armed soldiers and civilians who had helped themselves to the unlimited supply of weapons and now terrorised the streets. They robbed passers-by indiscriminately and murdered anyone who looked sideways at them. All it took was for one of the bandits to point and shout, “I know him—he’s a Pharaoh!” and the gang would surround him and deal out their version of justice. Army officers, policemen or gendarmes were treated mercilessly: once identified they were summarily judged, then shot, impaled on bayonets or beaten to death with rifle butts.

A particularly gruesome death awaited those who were caught near the frozen Obvodniy Canal.

I was crossing the Ismailovsky Bridge on a cold but sunny day when I saw a gang of about ten soldiers approaching. They were escorting an elderly general with a full beard, wearing dress uniform with a row of campaign medals. I melted into the crowd on the bridge and waited to see what fate would befall the unfortunate officer. The gang of killers stopped on the far bank and abused the general loudly, mocking his military decorations and making fun of his age. One of them pushed a cigarette into his mouth and ordered “Sakuri!” (Smoke!). The general spat out the cigarette and said “I don’t smoke”, but the leader of the bandits shoved the cigarette back in the old man’s mouth and lit it, along with his grey beard, which went up in flames. The wretched man screamed horribly, but the killers held his arms and let it burn while they laughed uproariously. At this point I recall that a platoon of armed soldiers passed by, but they ignored the unfolding tragedy because they knew that to interfere would probably mean their own deaths.

The overnight temperature had been -40°, the Obvodniy Canal was frozen to a depth of half a metre. A fishing hole had been excavated halfway across the canal. The bandits seized the general, dragged him to the edge of the canal and pushed him down the bank onto the ice. The old man tried to stand, but he was too weak. Four of the soldiers jumped down off the bank, seized him and dragged him to the ice hole. They lifted him by his legs and pushed him head-first into the water. After half a minute, they pulled him back up. The general gave a terrible death cry before they dunked him again… and again. When it was all over, his body disappeared forever under the ice.

I saw this and other barbaric methods of torture and execution repeated many times over the following days. None of the murders were investigated because there were no police stations any more, and in any case, the police themselves were the worst of the killers. On one occasion I joined a group of soldiers and citizens who were attempting to put a stop to the slaughter, but opposing these “murdering heroes” as they called themselves was a time-consuming and thankless task. The bandits hid in cellars and tunnels like sewer rats, and to eliminate one was to see a dozen more take his place.

HOTEL

The experiences of those few days left me both enervated and shattered. I had to be wary of who I talked to in case I gave myself away to bandit sympathisers and shared the same fate as the general and the captured gendarmes. Consequently my overwhelming emotion was a feeling of helpless loneliness. Petrograd was a large and unfamiliar city, and even more alien to me were its streets where bloody killers were running amok. I was grateful that at least I’d had the foresight to dress in a soldier’s uniform — it saved my life.

I hadn’t eaten anything since the raid on the delicatessen two days earlier. I spotted a group of soldiers who seemed to have some common purpose and I followed them to a building that had previously been a grand hotel. I asked what was going on? They answered that it was now an army mess.

A field kitchen had been set up in a vacant lot behind the hotel, and it was operated under strict army discipline, although there was no officer in sight (or none who would admit to being an officer). Two armed guards were posted at the gate and a Maxim gun was mounted on a two-metre high platform behind the food servery. A team of well-trained soldiers manned the loaded and cocked machine gun, which was trained on the entrance gates to deter rioters. The guards admitted 100 soldiers at a time, but only after they had surrendered their weapons. Their guns and ammunition were returned to them when they had finished eating, and they were told to vacate the area immediately. It took a long time to be served any food, but after the meal I had a full stomach, and I was just about asleep on my feet.

The doors of the hotel were open to everyone: the ground floor was crowded with soldiers and comprehensively trashed; the first floor was less crowded, though the mirror in the hall was smashed and the furniture was being burned to heat the rooms. There were no beds, so people dossed down on the floor. I found a free corner, pulled up my coat collar and put my back against the wall, but it was hard to sleep because of the shouting and singing, the quarrels and occasional brawls when weapons were discharged. But I was so exhausted, I eventually dropped off.

I woke early, surrounded by a shambles of the childish idiots who had interrupted my sleep. Some were now bleeding from fights or shots and some would never wake again. The air in the hotel was so foul that it was almost impossible to breathe, but I was just glad to be alive, to have escaped with no bones broken and food in my stomach.

HE’S A PHAROH!

I had always wanted to visit the Czar’s Winter Palace on the bank of the Neva, and I looked for someone to ask the way. The streets were almost deserted and the few pedestrians I saw were armed and probably dangerous. For that reason I kept to myself and as far away as possible from the marauders. At one stage I heard a distant shout, “He’s a Pharaoh!” followed by the sound of gun fire, and I immediately turned into a side street.

I spied a gang approaching me and I stood against the wall, trying to appear inconspicuous, but they turned right at the crossroads and, unlike the aimless murderers I had previously encountered that day, they seemed to have some purpose in mind. I followed them, keeping about 100 metres behind. Suddenly a machine gun barked and some of the gang were mown down. The deadly hail of bullets came from the cellar windows of a small house wedged between larger houses. The soldiers who hadn’t been shot had hit the dirt and were lying flat, trying to avoid the bullets. About six of the soldiers managed to crawl to the side of the road and gain the shelter of the wall, then they turned and sprinted towards me. I didn’t know how I’d react if they grabbed me, but they ignored me and disappeared around the corner. I stayed where I was and waited to see what would happen next.

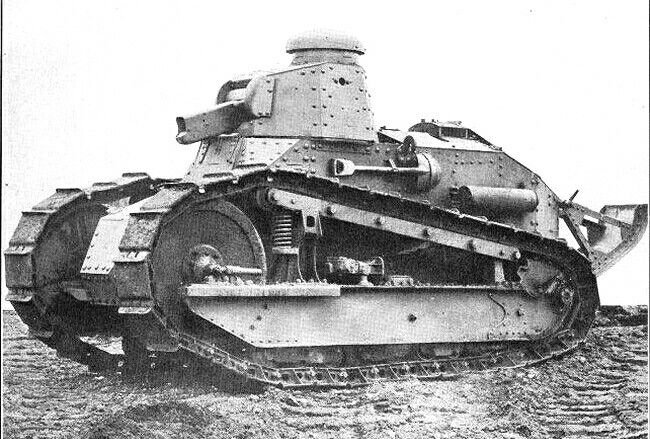

After half an hour, I heard a motor approaching and a tank appeared from around the corner, followed by a truck full of soldiers. The tank drove slowly down the middle of the road and stopped opposite the house with the machine gun in its cellar. The tank turned off its engine and stood immobile and silent as though waiting for a challenge. The Maxim gun responded to the challenge and started up again, firing at the tank, but the bullets simply ricocheted off the armour plating. The gunner in the tank swung the canon around until it was pointing at the Maxim’s position. It fired a shell directly into the basement window, and then everything was quiet.

Under cover from the tank fire, the soldiers jumped from the truck and took up fighting positions against the wall, then they broke into the house and we heard gunshots and grenade explosions. After 5-6 minutes, twelve men and one officer in gendarme uniforms were brought out into the street. The prisoners were lined up against the concrete wall and the machine gun on the tank began shooting, and within seconds they were all dead.

It struck me that, I for the first time in a week I had observed a disciplined military operation.

THE TOURIST

Later that day, I finally reached the Winter Palace13. In front of the huge building was an immense square, in the middle of which was the Isayevsky-Sabor (St Isaac’s Cathedral)14. Before the revolution, this church was reserved for the Czar and his family and anyone else wanting to enter required a special pass, but on this day nobody was there to stop me. The church was very high, but without a ceiling. A cast-iron spiral staircase let up to the roof where the bells were visible. However, the top of the staircase was very high and the exit was blocked off with iron bars.

I crossed the wide bridge over the Neva River and followed the road that led me to Vasiljevsky-Ostrov (Vasilievsky Island). Someone had been feeding and caring for the animals in the zoological garden and I spent the afternoon following a group of children around the cages and displays. I spent the next day at the People’s House (Narodny Dom) which contained dormitories, children’s playgrounds, a theatre, an art gallery, and a gymnasium, that all seemed strangely unaffected by the mayhem across the river15.

UNEASY PEACE

By the time I eventually found my way to Kronstadt Street, everything inside the headquarters building had been smashed or stolen. However, a field kitchen had been set up on the parade ground and a bonfire was blazing, even though it was a warm, sunny day. We were all emaciated and unshaven, but by the time we had something warm to eat, the atmosphere was generally happy and relieved. Soldiers and officers gathered in groups of 20-30, discussing what they had seen and experienced. Other groups simply gathered to tell jokes and sing. I reattached my officer’s epaulettes and was finally confident that nobody would call me out or attack me.

The exuberant conversation suddenly stopped and the jovial atmosphere grew grim as everyone looked towards the kitchens, unable to believe their eyes: our old commander, the Polish Lieutenant Rakey had appeared and was standing in the mess queue. The cook stopped serving, with his ladle in the air; all laughing and singing was silenced. But it was the silence before a storm, and I watched with baited breath to see what would happen.

The formerly self-important Pole turned nervously to the mass of soldiers surrounding him and said: “Friends, please forgive me. It was a different time when there was discipline…” But before he could continue his speech, the cook knocked him over the head with his ladle and the once cruel and arrogant officer fell to his knees in front of the soldiers and pleaded: “Please forgive me!” He announced that he was willing to take off his officer’s uniform and be no better than a common soldier, if only they would let him stay.

But there was no forgiveness: the soldiers took hold of his arms and yanked him to his feet. “Where’s the precious horse whip you beat us with?” Rakey had no answer. Then a large soldier punched him in the nose and several others joined in until his face was bruised and bleeding. No officer stepped in to stop the beating. The soldiers took him by the arms and dragged him to the gate, then one hit him with a rifle butt and he fell to the ground again. The soldiers didn’t chase him any further, but they roundly cursed him in words I don’t want to repeat here. The army career of this swaggering Polish officer came to an end in March 1917.

We organised a regimental committee and I was elected to be the new commander, but I asked for leave and fortunately it was granted. The Czar had abdicated and I was unwilling to serve the new communist government. I returned to Riga and reported to the Latvian High Command Ikolostriel and was assigned to the 5th Zemgal Rifle Battalion16.

POST SCRIPT

The revolution finally dragged to an end and order (of a kind) was restored. Once the fighting in the streets came to an end, it was possible to think about cleaning up the dead and wounded. The bodies were collected and a mass burial was organised in Marsovo Polye (The Field of Mars)17. The Petrograd Soviet planned to bury the bodies of several thousand soldiers at a single ceremony, in a long and deep trench blasted out of the frozen ground. A decree described in detail how “a row of corpses was to be laid side-by-side from one end of the trench to the other and covered in lime; then a second row laid out in the opposite direction, again covered in lime; and so on until the last of the fallen had been buried”. The idea of burying the fallen soldiers with neither coffins nor religious rites was so shocking that relatives hurried to claim the bodies and bury them in local cemeteries with religious rites. Eventually only 1,30018 of the fallen were buried in the Field of Mars. Red flags bedecked the square and the French anthem La Marseillaise was played.

MAP OF SAINT PETERSBURG AND GULF OF FINLAND

THE FEBRUARY REVOLUTION 8-16 MARCH 1917

- A series of public protests begin in Petrograd, which last for eight days and eventually result in abolition of the monarchy in Russia. The total number of killed and injured in clashes with the police and government troops in Petrograd is estimated around 1,300 people.

- 8 March (23 February) 1917: On International Women’s Day, demonstrators and striking workers – many of whom are women – take to the streets to protest against food shortages and the war. Two days later, the strikes spread across Petrograd.

- 15 (2) March 1917: Tsar Nicholas II abdicates and also removes his son from the succession. The following day Nicholas’ brother Mikhail announces his refusal to accept the throne. A Provisional Government is formed to replace the tsarist government, with Prince Lvov as leader.

FOOTNOTES

- Daugavas Vanagu Mēneštraksts, 1974 2(154) pp17-28

↩︎ - https://pixels.com/featured/october-1917-in-petrograd-boris-mihajlovic-kustodiev.html

↩︎ - Strelna village was a mix of private houses and dachas (summer villas), where senior officers were quartered. One large palace, Peter the Great’s Summer House, had been reclaimed by Czar Nicholas at the outbreak of the World War, when colonists of German descent had been forcibly evacuated to Siberia.

↩︎ - These military titles were common across Europe and are equivalent to the German honorifics “Ihr Wohlgeboren” (Your well-born) and “Ihr Hochwohlgeboren” (Your high-well-born)

↩︎ - 5 March in the modern calendar.

↩︎ - Kronshtadt Naval Base on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland. The Kronshtadt sailors were active in the formation of one of the most important Soviets in the summer of 1917. https://spartacus-educational.com/RUSkronstadt.htm

↩︎ - The Putilov Company (owned by Nikiolay Putilov). It produced both railway rolling stock and was the major supplier of artillery to the Imperial Russian Army. “In February 1917 strikes at the factory contributed to setting in motion the chain of events which led to the February Revolution. After the October Revolution it was renamed Red Putilovite Plant (zavod Krasny Putilovets), …The Putilov Plant was famous because of its revolutionary traditions. In the wake of Sergey Kirov‘s 1934 assassination, the plant was renamed Kirov Factory No. 100. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirov_Plant

↩︎ - The Column of Glory: 29 metres in height, a memorial to the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-1878, built from the barrels of 128 cannon salvaged from the war, mounted on a slab of packed rubble, topped by a bronze figure of Nike. http://www.saint-petersburg.com/monuments/column-of-glory-on-troitskaya-ploshchad/

↩︎ - Probably Trinity Cathedral http://www.saint-petersburg.com/cathedrals/trinity-cathedral/

↩︎ - The building Sterns describes may have been the Officers’ Club, in Liteyniy Avenue 20, now the Museum of the Leningrad Military District.

↩︎ - This could have been the bakery building of the Eliseyev Emporium complex, located at 56 Nevsky Avenue. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eliseyev_Emporium_(Saint_Petersburg)

↩︎ - The Cossacks were a proud warrior people who provided the Czars with a disciplined cavalry in return for land. WW1 and the 1917 revolution brutalised and weakened the Cossack community until they were devastated by the Civil War and Bolshevik persecution. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/cossack

↩︎ - From the 1760s onwards the Winter Palace was the main residence of the Russian Czars on the bank of the Neva River, this Baroque-style palace is now the main building of the Hermitage Museum.

↩︎ - “Isayevsky-Sabor” is Saint Isaac’s Cathedral. It is near the Winter Place, but not in its grounds. Today it is s museum of science. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Isaac%27s_Cathedral

↩︎ - Sterns seems to have combined a number of sites in his memory (60 years later). The Peter & Paul Fortress is the main feature of Valikyevsky Island https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasilyevsky_Island. The Narodny Dom was not on Vasliyevsky Island, but in Alexander Park, in the Petrogradskaya Storona https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Park. The zoo he refers to is probably today’s Leningradsky Zoopark, in Alexander Park http://spbzoo.ru/en

↩︎ - The Latvian Rifle Battalion was established in 1915. In 1917 it would have been fighting against the Germans, who had invaded the Latvian territory.

↩︎ - “ On March 5, 1917 (old calendar), the Petrograd Soviet decided to bury those who had died during the February Revolution on the Field of Mars.” http://www.saint-petersburg.com/squares/field-of-mars

↩︎ - This number is disputed. Ilya Orlov provides a plausible description in her blog: https://therussianreader.com/2014/11/13/ilya-orlov-field-of-mars/ ↩︎