Historical fiction; Hong Kong history; Canton uprising; Plague

ISBN9798870747385

The Kerosene Creek Mystery Book 2

“Hey Jindy, when you finish that China business, you come back here, ay” said Jimmy Sugarbag. Jindy Kelly arrives in the plague port of Hong Kong in 1894 She is looking for the enigmatic Johnny Fong, who may know the whereabouts of her mother. Her quest propels her from the heart of the British colonial establishment to the struggle for a Chinese republic. She discovers that Johnny is now a revolutionary outlaw, her mother is not what she seemed, and the answers to the mystery are back home in the socialist paradise of Kerosene Creek.

Blurb

In 1894, Jindy Kelly arrives in the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong at the height of the bubonic plague pandemic. She is searching for Johnny Fong, the boy she loved, and the truth about her mother’s disappearance. Her plans are thrown into disarray when she encounters an old enemy from her home town, and becomes entangled in a murder investigation. Her quest propels her from the heart of the British colonial establishment to the festering animosity of the Chinese slums. She discovers that Johnny is now a revolutionary dedicated to overthrowing the Qing emperor; her mother may not be the person she believed; and the answers she seeks were always back in Australia in the workers’ paradise of Kerosene Creek.

Excerpt

[Hong Kong 1894]

Jindy, Felicity [both dressed as nuns] and Old Hong, the gardener, set off along Caine Road, then swung down Ladder Street, but when they reached the steep and narrow lanes of Taipingshan District, they found their way blocked by a troop of British soldiers in crisp white uniforms and sola topis. The soldiers were carting armloads of rubbish out of the houses and stacking it in bonfire piles on the street. They were all smoking pipes or cigars to mask the gut-wrenching stink of garbage, fæces, pigs, and chickens.

“Step lively lads!” The red-faced Sergeant-Major rapped on the stack of broken furniture and rotting blankets and clothes with his swagger stick, “Burn this lot before the fleas cart it back inside.”

A crowd of women, children and old men watched mutely as a soldier sprinkled kerosene on the pyre and set a match to it. The flames caught quickly and licked upwards into a plume of black, acrid smoke. One of the women ran forward and tried to retrieve a smouldering quilt from the pile. A soldier pulled her back and she fell, clutching at his boots.

Jindy tried to intervene, “Sergeant-Major, why are you turning these people out of their houses? It’s not their fault that they’re poor!”

“Ah no ma’am, we ain’t the bailiffs. It’s the plague we’re rootin’ out of the ‘ouses. It breeds and festers in that filth. They should be grateful, but all we get is complaints.”

Felicity helped the woman to her feet, “They don’t understand why you’re burning their furniture. They think you are punishing them.”

The Sergeant-Major pointed to a tattered poster in English and Chinese fixed to one of the soot-blackened walls, “This ‘as been up a week. It alerts ‘em to expect us.”

“None of these people can read, Officer,” said Felicity.

“P’rhaps you’d do us the favour of readin’ it to ’em, Sis. It’ud make our job easier without all this carry-on.”

Felicity began reading the poster to the crowd in Chinese. A young girl of seven or eight tugged on Jindy’s veil and pointed at one of the houses being cleaned.

“Would it be all right if I go inside with her, Sergeant?” she asked.

“At your own risk, ma’am. Take care you don’t fall in a niffin’ hole or get bitten by a rabid rat. I’d never ‘ear the end of it.”

The girl led Jindy into the ground floor. Two soldiers were slapping whitewash on the blackened walls of the empty rooms. The ground floor had no floorboards, just damp and filthy packed earth.

“How many people live in this house?” she asked the painters.

“As many as the landlords can pack in.” The soldier pointed up with his brush. “I’ve seen rooms that once had ten-foot ceilings, they divided it up into two rooms with five-foot ceilings and a ladder between ‘em. No windows, no fresh air.”

Jindy followed the girl up a narrow staircase. The upper floor was subdivided into tiny rooms with no windows. A smaller room at the back served as a common kitchen, with a charcoal fire built on a layer of bricks. There was no chimney—the smoke had to find its own way out through the rooms and corridors and into the street. A soldier layering whitewash over six inches of encrusted soot was gingerly pushing an earthenware jar out of his way with one foot.

“What’s in that?” Jindy peered inside.

“Hold on Sister! I wouldn’t go too near without a cheroot under your nose!”

The stench of ammonia and shit was so strong that Jindy staggered back and had to lean against the wall to recover her balance.

“I’m dashed if I’m going to carry it down them stairs for ‘em,” said the soldier.

The girl darted into a room that the soldiers hadn’t cleared yet. In the gloom, Jindy could make out a woman frantically dragging quilts off the bunks and piling them onto an emaciated figure on a bed in the corner.

“Is he sick? I’m a nurse, let me look at him.” She tried to pull the quilt back, but the woman kept pushing her away and trying to cover the person up.

The Sergeant-Major looked in the door. “What’s goin’ on in ‘ere?”

“There’s a… a man, I think. He’s either sick or dead.”

“Don’t touch him, missus. It’s prob’ly plague.” He turned and shouted out the window into the street. “Body detail! First floor!”

Soldiers wrapped the body in the quilt and rolled it onto a stretcher. The woman wailed and beat her head with her hands while the young girl stood silently in the shadows

“We’re under orders to take anyone we find with plague to the ‘orspital. Or the Kennedy Town morgue if they’ve snuffed it. But some of ‘em try to ‘ide the bodies from us.”

“You wouldn’t believe the lengths they’ll go to,” said one of the stretcher bearers, “One place we went into, we saw four geezers playing mah-jong ‘oo refused to move. We found out why—one of ‘em was a bloody corpse.”

“Yea, and ‘ere’s the thing—he was winnin’!” laughed the second soldier as they manoeuvred the stretcher down the stairs

The Sergeant-Major shouted, “Everythin’ in this room is to be burned. You got that?”

Outside, Felicity was still explaining the poster to the residents.

Jindy said to the Sergeant-Major, “I think hosing the rooms out with water would be more effective than painting over it.”

“There’s no running water here, just wells.” He pointed to a hole in the ground beside the house. The water was about six feet down, black, with a rat calmly paddling through the floating rubbish. “If you asked me, they’d do better to burn the whole of sodding Taipingshan to the ground,” said the Sergeant.

“But ‘oo the ‘ell wants to know my opinion?”

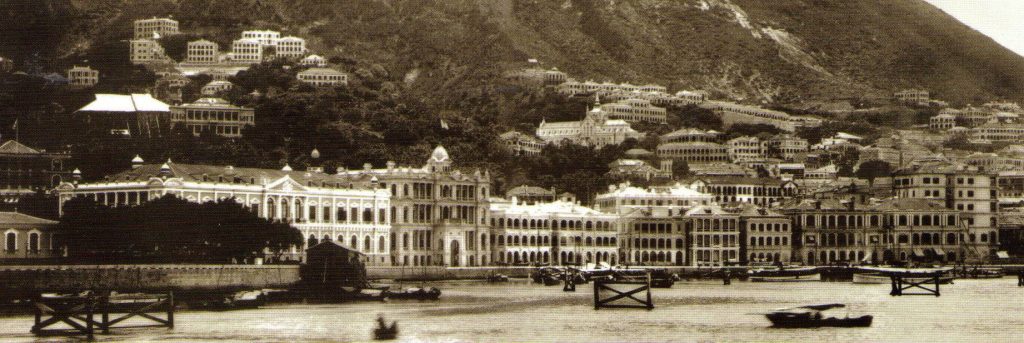

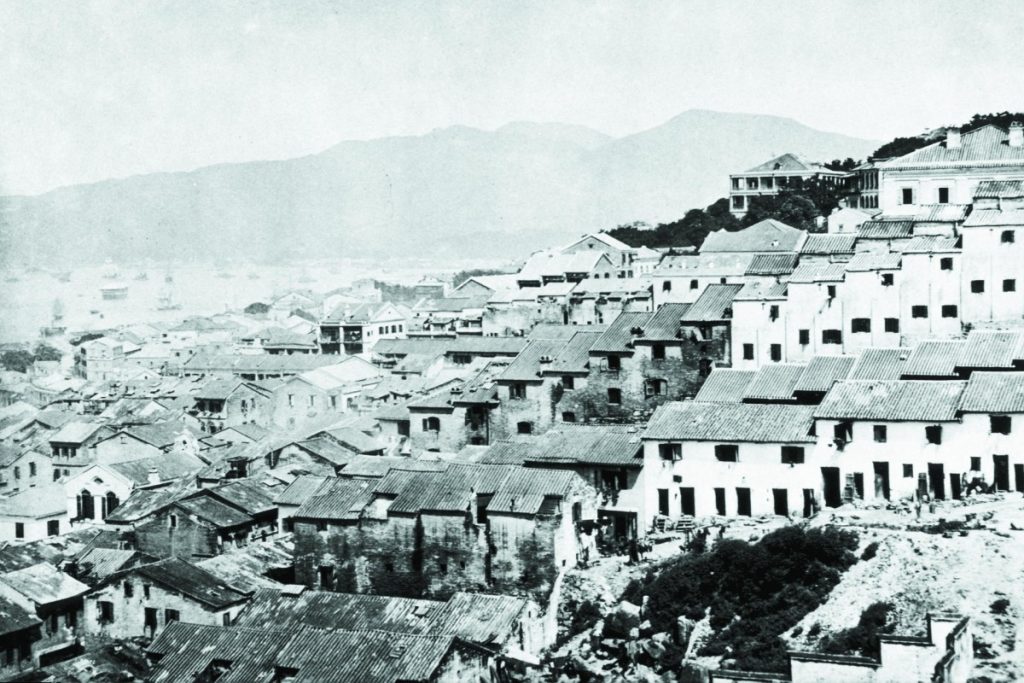

Research photos

A few images of Hong Kong scenes in the 1890s