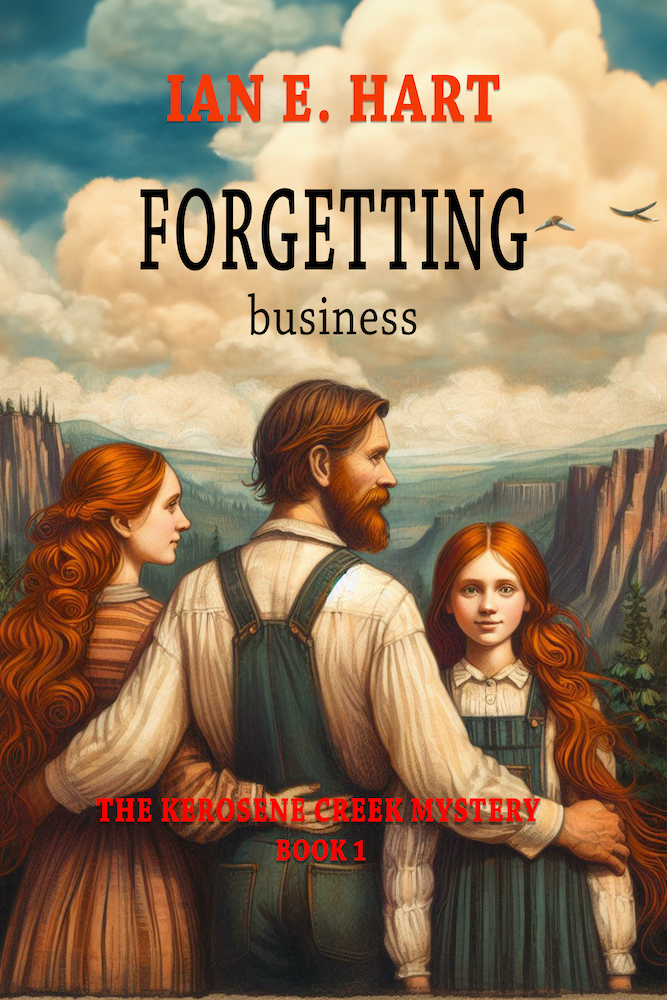

Historical fiction; Psychological mystery.

ISBN: 9798870661070

The Kerosene Creek Mystery, Book 1

“Hey Jindy, I hear you got that forgetting business,” said Jimmy Sugarbag. The entire population of Kerosene Creek village disappeared overnight and Jindy Kelly can’t remember a thing about it. Sister Thomas calls it “hysterical amnesia”. They take her back to the ghost town where she confronts the traumas that wiped her memory: the insanity of the Irish commune leader, the betrayal by her oldest friend, the disappearance of the Chinese boy she loved, and her Ngunnawal mother, condemned to hang for witchcraft and murder.

Blurb

In July 1888, the entire population of the Southern Highlands village of Kerosene Creek disappear without trace. A month later, a young woman appears on the steps of Saint Bridget’s Convent, starving, distressed and mute. Her name is Jindy Fiadh Kelly and she appears to be the sole survivor, but she has completely lost her memory. Aboriginal tracker Jimmy Sugarbag calls it “forgetting business”. Amateur psychologist Sister Thomas diagnoses “hysterical amnesia,” and she believes that recovering Jindy’s memory may hold the answer the Kerosene Creek mystery; but Jindy’s burning need is to discover the fate of her Ngunnawal mother. The three of them return to the abandoned village, where Jindy re-lives the madness that led to its destruction: the warped socialism of the Irish commune, the paranoia of its leader, the eccentric band of homesick Chinese revolutionaries who stumble on a hoard of stolen gold, the devastating betrayal of her oldest friend, and her mother’s unjust arrest and trial for witchcraft and murder.

It is a story about longing, loss and the labyrinth of memory, through the eyes of a rebellious young woman with a lust for life and a wicked sense of humour. It is set against the religious and racial prejudices of a country that is about to become Australia.

Read Excerpt

At 6 o’clock on a Sunday morning in 1888, Sister Mary Frances unlocked the front door of Saint Bridget’s Convent in the southern highlands town of Berrivale to find a thin and shivering young woman huddled on the front steps. She was dressed in a stained and singed pinafore, and her arms and legs were covered in scratches and scabs. A battered carpet bag lay at her feet, and her right hand clutched something so tightly that blood was seeping from between her fingers. But Sister Frances’s most enduring memory was of the girl’s shock of startlingly red hair. A note was pinned to her dress.

To the Abbess, Saint Bridget’s Convent,

Dear Mother Jerome,

The girl’s name is Jindy Fiadh Kelly, about 16 or 17. She is believed to be a survivor of the Irish Commune Incident. She appears to have undergone a great shock, as a result of which she has lost the power of speech.

Father F. X. O’Brian

Sister Frances brought the urchin to the Abbess, who attempted to question her, but the young woman appeared untethered to the physical world and did not know where she was or even who she was. They called the doctor, who treated the deep scratches on her wrists with Mercurochrome, waved his hand before her eyes, and described her state as “catatonic”. Everyone had an opinion about what to do. Sister Agonistes suggested exsanguination, which had produced results in the past in cases of demonic possession, but the girl was so pale it was doubtful she would survive any further loss of blood. The doctor prescribed a stimulant and recommended she be confined for the time being in a darkened room. The nuns stripped off the ragged garment, sponged her down, bandaged her wrists, dressed her in a clean calico shift and tempted her to eat a few mouthfuls of porridge and sweet tea—all the time attempting to question her about her origins and what she remembered. Sister Matilda gently prised open the fingers of her right hand to reveal that she was holding some kind of talisman: a half-moon shaped green stone carved with the likeness of the head of a goat or some other horned animal. When Sister Matilda reached for it, the girl began screaming and bit the nun’s finger so deeply she later required stitches. Her screaming continued, and she fought, scratched, and bit anyone who tried to touch her and she was so strong it took four of the largest sisters to restrain her. The nuns locked her in the cellar with a cot, a horsehair mattress, and a bucket, and pushed food to her through a flap in the door. She continued her recalcitrance by refusing to lie on the mattress—preferring to curl up on the ground in foetal position, wrapped in a blanket. The nuns took turns praying outside the door for the Devil to release her soul, and eventually the girl stopped screaming and reverted to her catatonic state, though she continued to refuse the bed. Once a week, the same four sisters carried her to the bathroom, washed her with coal tar soap and changed her bandages and shit-stained garments.

Jindy ran away three times in the first two months. The first time Sister Matilda gave chase on her bicycle, put her in a head lock and frogmarched her back to the convent. The second time they found her at the Iron Works, sitting up in the manager’s office taking tea like a lady. The same four sisters escorted her back, but they did not notice she had stolen a box of Vestas, and she started a fire in a charity box of clothes. The third time she was returned to the convent by the police, trussed like a chicken across the back of a horse. The prison guards had spotted her in the branches of a fig tree that overlooked the wall of the gaol. She was waving and making hand signals to one of the prisoners, later identified as the blacksmith Malachy Kelly, who was serving 20 years for manslaughter and wanton destruction of property.

The police identified the girl as the daughter of the prisoner Malachy Kelly. They were both survivors of what the newspapers were now calling “The Kerosene Creek Mystery”. Her mother was May Kelly who had earlier been tried and condemned to hang for witchcraft and murder.

“Where were you trying to run away to?” the nuns asked her each time she was returned to the convent. And every time, Jindy would point to the West. “There’s nothing in that direction but stinging nettles and wild black cannibals who’ll put you in their cooking pot.”

Jindy’s answer to every question was to croak “Ma,” like a sheep. They eventually realised she meant “Mother.”

“Your mother is dead, Jindy,” they would repeat. “Get that into your fat head.”

A dead mother and a reprobate father were nothing new to the nuns of Saint Bridget’s. Most of them had been brought up on struggling farms with a drunken father, a worn-out mother, a dozen brothers and sisters, not enough to eat, no education and little prospect of a husband. Marrying a daughter off to the Lord Jesus meant one less mouth to feed. For the daughter it was a welcome escape from poverty, incest and violence.

Once Jindy gave up screaming and biting and began speaking, she was put under the charge of Sister Agonistes, the convent’s zelatrix, who had spies everywhere and eyes in the back of her head. Sister Agonistes had been raised on a sheep farm in the Snowy Mountains where she was familiar with breaking in wild brumby horses. “By the time I finish with you, my girl, you will thank me for thrashing you, and be able to rattle off a Rosary as fast as Beelzebub.” (Beelzebub was the convent’s pet cockatoo.) But even Sister Agonistes failed in persuading Jindy to sleep on the bed. The zelatrix experimented with tying Jindy down, but the girl’s screams and struggles were so agonising and went on for so long that Mother Jerome requested that they let the orphan have her own way.

The nuns never discovered how Jindy managed to run away, for the reason that the cellar where she was imprisoned was haunted. Sister Agonistes had once encountered the ghost of the last Mother Superior there, “Naked and on her knees, mortifying her flesh with a scourge knotted with glass shards so that her back wept with the blood of the crucified Christ.” Consequently, the nuns avoided the cellar and Jindy was free to roam the dark and musty catacomb unsupervised. She discovered behind a pile of old furniture, rusty agricultural implements and broken plaster saints, that there was an awning window large enough to crawl through. She made use of her private exit to roam the streets of Berrivale at night and the ghost-like figure with bright red hair frightened the bejaysus out of many an Irish drunk.

After two months the nuns became bored with Jindy’s monosyllables and stubbornness and gave up trying to save her soul. The effect was miraculous: when they stopped pressuring her to speak, she began talking; when they stopped forcing her to eat, she revealed that she had table manners; when they stopped rubbing her nose in shit, she began to use the bucket; when they unlocked the door to her cell, she stopped running away. Sister Agonistes gave up trying to discipline her and decided her time was better spent stalking the dormitories in search of blasphemers, masturbators, and bed wetters. However, Jindy still refused the bed, though she was willing to lie down on a bed of straw.

Research photos

Some historical photos of the ghost town of Joadja and environs in the southern highlands of NSW—the inspiration for the fictional village of “Kerosene Creek”.